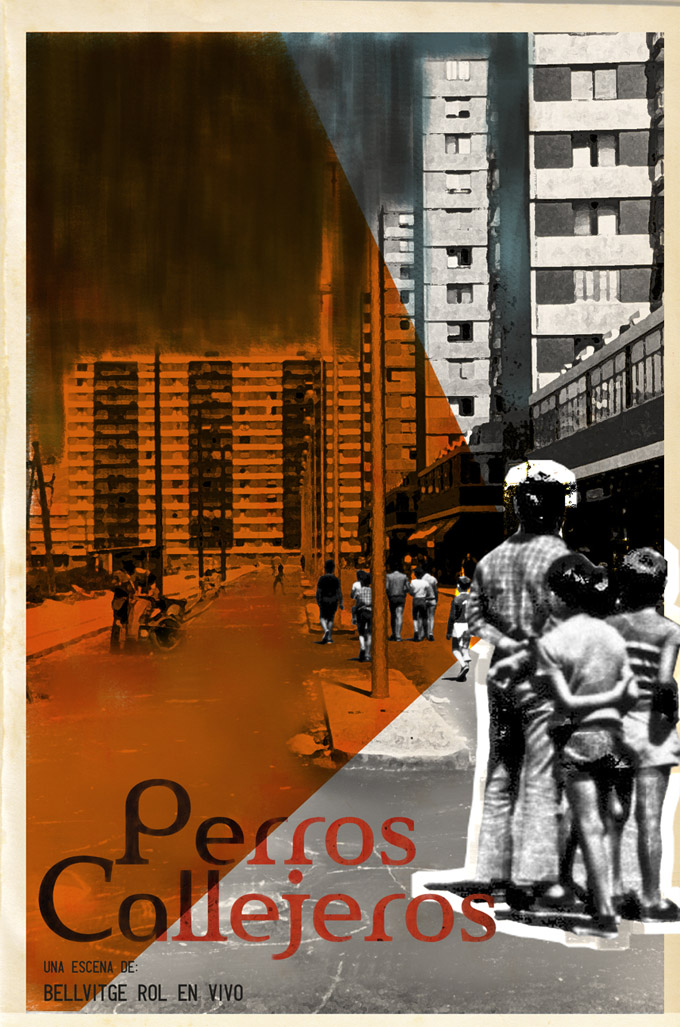

We are working simultaneously on the next two scenes of

Bellvitge live role-playing

: Street Dogs and

Works and Days

. Here is a brief reflection on how we approach the first of the two:

On many occasions, listening to its own protagonists, neighbors who have lived in the neighborhood since its construction, it seems that the historical account of Bellvitge ends in the 80s —as does that of many working-class neighborhoods in the Spanish state—. Among other reasons, the emergence of strong social problems such as juvenile delinquency or drugs, means that the entire decade is glossed over. In part, films like Street Dogs contributed to building and installing in the collective imagination representations of urban peripheries in which they appeared as dangerous territories and their inhabitants as savages and criminals. The demonization of subaltern groups —whether due to class, race, gender or other issues—, their lifestyles and the territories they inhabit was nothing new in the late 70s nor has it disappeared today; even today negative prejudices and stereotypes about the neighborhoods of the urban peripheries are reproduced and circulated.

We could say that the 80s really begin at the end of the previous decade with the first democratic elections of 1979. This milestone marks the end of an intense cycle of struggles during which the idiosyncrasy of neighborhoods like Bellvitge was forged. It is at that moment when the neighborhood leaders join the governing bodies and the public administration and a more or less tacit non-aggression pact is established with the nascent democratic institutions. It is significant that the last major neighborhood mobilization in Bellvitge ended around 1977 when it was possible to stop the construction companies’ plans to build more blocks of flats in the neighborhood —a historical moment that we reflect in the scene

Boycott of the works of our role-playing game—.

With the institution of democratic city councils —and especially in the city councils of the progressive left, which were the majority in the urban peripheries— a series of social policies were launched that aimed to address problems such as those mentioned and that until then had been repressed or treated as an object of charity. These policies had contradictory or, at least, paradoxical results, since although they partially mitigated the consequences of social inequality, on the other hand they established a whole series of mechanisms that singled out and categorized young people from the neighborhoods of the periphery mainly as passive subjects and victims of their circumstances without the capacity for agency and to transform their reality.

In the

debate after the screening of the documentary video The young people of the neighborhood, filmed by the

Video-Nou collective in the neighborhood of

Canyelles (

Barcelona) in 1982, which we screened at the

Institut Bellvitge last April, the philosopher

Jorge Larrosa pointed out how the film portrayed young people and their context as a list of problems: delinquency, unemployment, school absenteeism… the video does not refer to any of the forms of self-organization, collective empowerment and autonomy that characterized life in the neighborhoods of the periphery. It is significant that the documentary was commissioned by the

Barcelona City Council itself. In that same debate

Antonio Rosa, a social educator and member of various entities in Bellvitge since the 70s, brought up the term

pre-delinquent that was applied from social assistance programs to certain young people based on a series of

indicators. In a way we can say that the categorizations and jargon used by educators, assistants and social workers also contributed retroactively to fixing a certain imaginary about the young people of the neighborhoods.

Thus, the public administration deployed a whole series of resources, knowledge and technologies that replaced the self-organized action of the neighbors, while functioning as control and disciplinary devices. In this way in L’Hospitalet, in 1979, the Register of Beneficence inherited from the Franco regime is eliminated and the Social Services are decentralized, assigning a social worker to each district. Likewise, the Department of Social Services commissions the Obinso group to carry out an investigation into juvenile delinquency in the city, carried out by the sociologists Lluís Ventosa and Lluís Recolons.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the residents of Bellvitge, whose identity was built in the struggle to dignify their living conditions, refuse to talk about a moment in their history that is associated in a simplistic and exclusive way with crime and drugs and in which neighborhood mobilization ceased to have a relevant role in the public sphere —it is significant, for example, the open debate then about neighborhood associations that some people considered unnecessary once the parties had assumed political power—. In a way we can understand these events as repressed traumas that are not talked about and that are relegated to a lower stratum of the collective memory of the neighborhoods.

With this new scene of Bellvitge live role-playing we propose to address the memory of the neighborhood in those years and we ask ourselves how to do it: in the first place it seems necessary to highlight the political, social and cultural complexity of the moment and oppose it to any simplistic account. The mere chronicle of more or less sordid events is as inaccurate as a sweetened portrait in which only positive aspects are focused on; this does not mean that it is not necessary to do an “archaeological” work that “rescues from oblivion” initiatives and people who played a prominent role in the configuration of the neighborhood at that time.

The beginning of democracy in the early 80s brought with it a cultural explosion that in L’Hospitalet had its most vivid expressions in the Culture Classrooms of the districts. In Bellvitge, for example, the Culture Classroom experiences moments of effervescence in which neighbors, in collaboration with Nelly Peydró, who was director of the Classroom between 1979 and 1984, take the public sphere and the street through cultural practices after decades of repression and censorship.

The macguffin of Street Dogs (the scene of Bellvitge live role-playing) is precisely one of the final scenes of the film Street Dogs directed by José Antonio de la Loma in 1977. The development of the plot, which we will not reveal yet, will serve to establish a conversation (rhizomatic, decentralized…) about all these political, social and cultural aspects. The scene (from the film) was shot precisely in Bellvitge, to be exact in front of the Lumière cinema, a room in which it would be screened years later to the great delight of the public. Our scene (the one from the role-playing game) will start right at that moment and place, with the audience of the Lumière cinema watching the end of the film Street Dogs in the early 80s. Upon leaving the cinema, an unpredictable series of events will unfold… stay tuned to your screens!

If you want to collaborate on Street Dogs contributing your personal testimony, documentation, images, participating in the creation of the characters, the plot or in the production of the props and set elements or simply playing get in touch with us. Any contribution will be welcome :D!

The first game of this scene is scheduled for mid-February 2015, coinciding with Carnival. We are waiting for you!