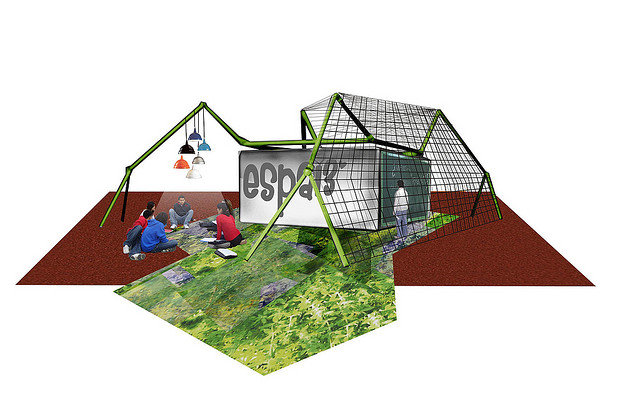

The future EspaiDer projected by Cataqsis based on work with students

For some time now, we have been reporting punctually on the various presentations we have been making of projecte3*, in which the project has been mostly received with interest and even, in some cases, with enthusiasm. Bringing this up is not now an exercise in self-satisfaction; on the contrary, we want to offer a counterpoint to the difficulties, practically insurmountable, that we have encountered during its realization.

Very briefly, projecte3* is a proposal from LaFundició to the IES Joanot Martorell in Esplugues de Llobregat to establish, together with students and teachers, a process of research and analysis of the spatial, temporal, and curricular arrangements that organize daily life in an institute, and which are, for the purposes of reality, those that reproduce the power relations that exist between individuals and that run through them and organize the way in which the legitimacy of knowledge is distributed, the possibility of producing it and, what is equally important, the possibility of not reproducing it. projecte3* also proposed to materialize, and even to say objectify, an alternative proposal to these provisions, based on prior reflection and realistic consideration of the possibilities of transforming them. In practice, this translates into many sessions of debate, group reading, mapping of space, and analysis with students, trying to apply a methodology (or rather an attitude) that would allow collaboration and the collective construction of knowledge. Our intention was (and is) that this alternative proposal be carried out in its entirety, that is, that it include the physical construction of a new space, which would no longer be a classroom and which would be added and associated with the main building of the institute. In this section we have the wonderful collaboration of the group of architects Catarqsis and Santiago Cirugeda.

We thought this was a consistent way to act, a way to get to the root of the matter. It is now evident to us that, with the exception of Isabel Capdevila, Head of Studies of the Institute (without whose understanding and support it would not have been possible to even start the project), the proposal was not understood or assumed as their own by the management of the center. Not even so long after, as during its presentation to the School Council, in which the installation of the prefabricated house of 42 square meters that would form the embryo of the future space was approved (which would end up being named EspaiDer3*). Already during that council, José María Primi, director of the institute and main person responsible for the cancellation of projecte3*, made it very clear that what happened in that space should be managed, supervised, and authorized by the teaching team, flatly denying just what had just been proposed. Days later, the management of the center would deny the installation of the modules in the courtyard of the institute, as approved in that school council. The modules were located in an adjacent vacant lot, supposedly owned by the institute (a point that no one anywhere has been able to confirm) on the condition of being removed in the shortest possible time; days later the director denied Santiago Cirugeda entry into the institute, claiming that if the architect was an important person “he was more so.”

There are many lessons that, in this empirical, if not traumatic, way, we have learned about the functioning and organization of education during these months of work, negotiation, and “resistance.” And also about the way in which educational policies are inserted into public life in general. Possibly two should be highlighted: on the one hand, that the democratic organization of educational centers is no more than a rhetorical exercise and a staging, as demonstrated by the fact that the will of a few people can prevail against that of the students themselves and even of the parents who supported the project – despite the efforts of the center’s management to “hide” the conflict situation in which it had ended up; even more, we have been able to verify how the public administration, far from trying to mediate and seek solutions, in an unreflective and automated way has put in place a whole series of bureaucratic devices that have reinforced the position and the oligarchic decision of a faction of the board of directors of the center. On the other hand, we have learned that ‘innovation’, so requested and touted from the general education plans and policies, is inapplicable in educational centers when it involves a real transformation of the structures that govern their operation, even if it is done experimentally and as a pilot experience.

As we say, it would be very long to explain the succession of delirious situations in which we have been involved in our effort to rethink the project outside the institute as a cultural and educational space managed by the youth association EspaiDer3*, founded by a group of students who participated in projecte3*. We now depend on the authorization of the L’Hospitalet city council to install the modules on privately owned land, a point that is not at all clear for now.

As we announced a few days ago, we are posting here the Spanish version of the text originally published in English in number 15 of the TkH Journal, a Spanish version that will appear soon in a monographic publication of the Aulabierta association dedicated to collective pedagogies. Aulabierta is a project that we have already talked about extensively in this blog and whose existence, we think, reaffirms our conviction that projecte3* is not a utopian, absurd, or negligent initiative.