We distrust the epic: we suspect that the epic tale hides something from us.

On the one hand, the epic narrative hides the social production tasks necessary to sustain the life and work of its protagonists (assisting, cooking, cleaning, caring for the children, loving, consoling, listening…) Feminized tasks in many cases, which rarely appear in the epic tale; the quartermaster or the rearguard of the battle is rarely mentioned. But we will talk about this more extensively at another time.

On the other hand, the epic tale makes invisible what is lost in victory. We will elaborate on this here regarding the second scene of “Bellvitge live role-playing” that we have titled “The boycott of the works.”

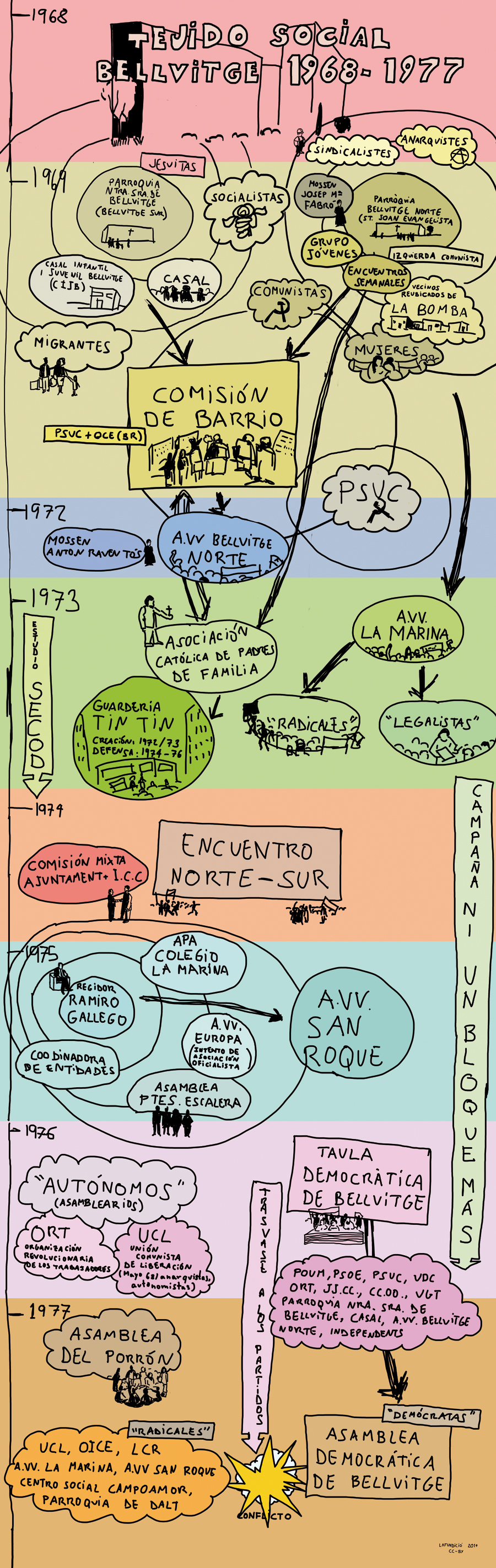

Since we became interested in the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Bellvitge neighborhood, in the ways in which its memory is constructed, we have had that suspicion. In Bellvitge, as in so many other working-class neighborhoods built in the heat of development in the late 60s and early 70s, a hegemonic vision of the neighborhood is shared, a seamless story that runs from mouth to mouth, which you can hear as soon as you ask any neighbor about their memory: when they arrived there was nothing, no services, no facilities, no asphalt on the streets, no parks, no sewers… there were only blocks, mud and rats; it was thanks to the tenacious struggle of the neighbors, to the protest actions —such as the one that inspires “The boycott of the works”— that they managed to dignify their living conditions.

Careful! it is not that this story —which, on the other hand, the established voices of the neighborhood also take care of amplifying and disseminating— is false, not at all!: the people who fought to improve the neighborhoods, who dedicated their strength and their creativity, who truly risked their lives! deserve all our respect and recognition.

The problem is another, the question is not of the order of truth, but of what is made visible or not, of what is focused on or not: we can say that the end of the Franco regime was accompanied by the demobilization of neighborhood associations; the left-wing parties, which in clandestinity had supported and promoted neighborhood struggles, undertook a policy of social pact in order not to destabilize the nascent and fragile democracy. The neighborhood movements were subordinated to the electoral logic of the parties —and in fact, not a few neighborhood leaders went on to integrate into their command structures first and to occupy public office later—.

Later, already in the 80s and under a socialist mandate, cultural policies democratized access to culture, but in turn had the pernicious effect of neutralizing those experiences of citizen self-organization in the management of the social and cultural life of the neighborhoods, and ultimately, would turn culture into a consumer product.

Social conquests were achieved by claiming rights from the administration, claiming facilities and services, but they were also achieved by taking them: through autonomous forms of organization, social, cultural spaces and public services were created where there was nothing.

These are issues that barely emerge in the story of the history of the neighborhood and that do not have a substantial presence in the collective imagination. In fact, on many occasions, talking with neighbors, the history of the neighborhood seems to end in the late 70s. It would seem that at that time the bulk of the social conquests had been achieved and that everything that came after was not worthy of mention, that it did not deserve to be narrated because it lacks the epic necessary to create social consensus.

Democracy was established at the price of a consensus that was not such: in Bellvitge, again as in so many other neighborhoods in the urban and working-class peripheries of the Spanish state, divergent voices were heard then, “radical” groups and movements that did not accept the price to pay for democracy; among other reasons because the change of regime did not entail an immediate and substantial improvement in the living conditions of the most impoverished classes. The new “space of coexistence and freedom” that democracy opened, opposed to the ideological polarization that had led the country to confrontation, was sustained —and has been sustained until today— in a specific regime of representation that demarcates what is visible, sayable and thinkable.

It is not about “reopening wounds”, making use of an expression habitually used to sustain that regime of representation that we were talking about, but about incorporating difference and multiplicity into the story or, rather, into the stories.

The events on which “The boycott of the works” is based constitute one of the greatest achievements of the neighborhood struggles in Bellvitge: thanks to the protest actions, it was possible to paralyze the construction of 29 of the 32 buildings planned; however, those three buildings that were finally built highlighted the differences between the sectors of the neighborhood that accepted their construction in order not to jeopardize the achievements made, and those who advocated not yielding an inch in compliance with the slogan «Not one more block», which had led the protests until then.

The past is not something that we only remember (to repeat it or not to repeat it); the past is something that we build and that acts in the present, that affects us now and that is part of our becoming.